Local History Articles By Mervyn Edwards

TERRY WALSH ON FIFTY YEARS OF RADIO STOKE

(For The Sentinel's The Way We Were, April 14, 2018).

With Radio Stoke having reached a perky fifty years old, I recently spoke to the ever-chipper presenter Terry Walsh about his own broadcasting memories. So how did Terry develop an interest in radio? He responds:

"I started on BBC Radio Nottingham's youth programme while still at school, after my scout leader suggested I get involved. Eventually, aged 20, I worked for them part-time. I then went to work for Radio London but landed a job at Radio Stoke when I was 21. I'd never been to Stoke before - so my first experience the city came in October, 1974. My new job at Radio Stoke was as a station assistant - we call them broadcast assistants today."

Terry assisted producers and presenters and made the coffees, but was gradually introduced to presentation, announcing the late opening chemists' lists or the fishing reports. Enjoying this very much, he pushed to become a presenter and within a couple of years was presenting programmes and occasionally reading the news reports.

"By 1976," he smiles, "I was presenting on a very regular basis - perhaps two hour music programmes or I would go out reporting. "When I worked in London for TV, I would approach people and talk to them in the street, and they would reel back as if you were weird. In Stoke, you can talk to anyone in a bus queue and no one thinks twice about it. Getting to know Stoke was a steep learning curve, but my ability to mix with people was an advantage.

"It was a shock coming to Stoke initially on account of the industry here. Stoke was grimy and dirty, with its potbanks, pits and steel works. I recall catching buses or driving through the city at lunchtime and seeing the pottery workers sitting outside by the roadside, reading newspapers and smoking fags."

Terry has fond memories of many former colleagues:

"The very first news editor at Radio Stoke was Tony Inchley, who came from Somerset and had a very distinct accent. He knew all the politicians locally and was interested in political news and then there was Arthur Wood, the Education producer, who was passionate about local history and those two had more influence on me than anyone."

He recalls many other colleagues including Gordon Astley, Sandra Chalmers and Sam Plank:

"I didn't know Sam Plank when I first started at Radio Stoke, because he started in the 1980s and I'd gone off to work on TV production at that stage. However, I returned in 1990 and got to know him well as an enthusiastic chap who would talk to anybody and raised a large amount of money for local causes. In his own way, he was very influential in the area. It was sad when he died, but he left his mark. He wasn't just an entertainer, he cared about people as an individual - and that's a real skill, the key to good broadcasting in my opinion."

Broadcasting was once a very formal business, and Terry has observed many changes.

"In the old days," he opines, "many presenters had degrees or were university educated, but nowadays, they're more likely to be products of real life, with other skills outside of broadcasting. Perhaps they've worked in local shops, as did Stuart George, or in teaching and may have drifted into broadcasting almost by accident - but they are passionate about the area. We're encouraged to get out of the studio and present live material rather than present clinical, perfectly-edited radio. It's warts and all broadcasting, which represents real life.

"A broadcaster should have empathy with other people and must have lived in the real world - been through upsets, family issues, the deaths of friends. Some of our presenters talk about their issues at home, perhaps bringing up teenage children. When they talk about it on radio, listeners know exactly what they've been through. Presenters such as this are not looking for sympathy, merely proving that they live in the real world, and that they have knowledge and experience. In this way, Sam Plank was a top broadcaster, and Paula White is, because of the issues she has had to deal with in life.

"I've only worked in the media, and lack certain knowledge, but I've had a lot of life experience. I'm not a parent, but I can change nappies and I'm a very good uncle and I've travelled all over the world and seen how other cultures work. I can talk about things and understand what people are going through."

But can a radio presenter be an uplifting influence, even a role model?

"We all have role models," replies Terry, "and I wouldn't want to let anyone down. So you can't be a role model all of the time."

"However, I'm 65, and still a fit man who plays squash three times weekly. I think in the manner of someone twenty or thirty years younger, and yet have the experience of age."

At fifty, Radio Stoke can also claim to have the experience of age. So Happy Birthday to our local radio station!

MEMORIES OF THE SCRATCH

(For The Sentinel's The Way We Were, February 17, 2018)

Smallthorne people didn't call their cinema the Bug Hut or the Flea Pit. They had to be perverse. They called it the Scratch. The cinema opened in 1914 and later became a bingo hall, but when I took the attached photograph in June, 2003, demolition of the tumbledown building was imminent.

You can patch together a history of the picture house through newspaper references, but for a real whiff of cinema history you cannot beat the memories of those who patronised these temples of entertainment. Smallthorne-born artist and painter Arthur Berry recalled the Scratch in his book, A Three and Sevenpence Halfpenny Man. Berry describes, with typical gusto, his wonderment at discovering the cinema for the first time in the 1930s: "I never dreamed such a world existed. It was a new dimension of reality." He and his bubble-gum chewing pals sat on the wooden seats at the front of the auditorium and watching films starring Tarzan - the king of the jungle, and Berry's hero of heroes. He also recalls the cowboy films starring the likes of Buck Jones and his white horse Silver King. Arthur enjoyed them immensely, with one reservation: "There was usually some young woman in them and she mostly ended up getting kissed. This I could not stomach in any way as at that time I had no understanding of the way the world worked."

Several local people talked to The Sentinel in 1999, offering their own memories of a misspent youth and recollections of the Scratch. Dorothy Breslin (nee Askey) knew it in the 1950s. "It was the local meeting place for young lovers and there was nowhere else to go for recreation," she opined.

Brenda Isaacs worked there as an usherette in her twenties. "I was courting somebody at the time and I was going there for extra money," she revealed. "I worked in a potbank during the day and at the cinema at night. It was a nice place, but the wages were only a pound a week. I remember the first wage I had from the cinema was a pound note and it blew right out of my hand in the street. I had to chase all over Smallthorne after this pound, but I got it."

Derek Bassett of Werrington travelled from his boyhood home in Bradeley to visit the cinema. He mused: "It was quite a little place, with wooden floors rather than carpets. If you paid to go upstairs and walked along the back row, you could cut off the light from the projector. They only had the one projector, so when they had to change the reel, the film stopped."

However, my favourite memory of the cinema in the 1950s was provided by Paul Nixon of Werrington:

"There was never any fighting or trouble, but you would take the mickey out of the film, because you would probably have already seen it.

The funniest thing we ever did was when we took over a row of eight seats.

One of the lads had a screwdriver and took the screws out of the entire row and replaced them with matchsticks.

We then skipped over to the other side of the cinema and waited.

This bloke came down, he must have been fifteen stone, and when he sat down the whole row went over.

There was dust everywhere, and we all got chucked out. It was the funniest thing I ever saw."

FREED FROM THE DEMON WEED

(For The Sentinel's The Way We Were, February 3, 2018)

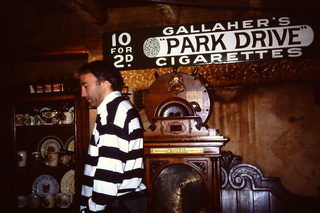

The ban on smoking in public places, introduced in 2007, has done much to improve public health, but it was not so very long ago that people smoked at the football match, the pub, the cinema and on public transport. Smoking was first allowed on railway trains in 1860. Smoky trains displeased non-smokers, hence the government passed the Railway Bill in 1868 which introduced smoke-free carriages.

The North Staffordshire Railway Company built a magnificent railway station at Stoke in 1848 - but what was it like to travel on the Knotty's lines? A letter to the local press in 1870, sent in by Anti-Smoker, complained about smoking in those railway carriages where notices had been put up asking passengers not to smoke. Smoking had become so normalised, that station masters and guards were not enforcing the bye-laws. Another letter was received by The Sentinel in September, 1875. The reader remarked that winter was approaching, and that: "We must either be content to sit, while riding, with open windows, or breathe an air polluted by tobacco smoke. Although separate compartments are provided for smokers, yet in nearly every other carriage is smoking allowed, in opposition to the laws of the company. As a regular passenger, I strongly protest against being annoyed by tobacco smoke." Even as long ago as the 1880s, there were regulations in regard to smoking on trams, which is why, in 1887, William Walklate, a tipsy collier, went to court for refusing to extinguish his pipe and for swearing on a local tram. Later, buses suffered the same annoyances.

In 1942, a workers' bus was taking workers to Chatterley Whitfield Colliery when Wilmott Cotterill, standing in the gangway, took offence to the smell of the pipe being smoked by Percy Jones, who was sitting down. Cotterill ordered Jones to extinguish his pipe, or he'd knock it down his throat. He consequently hit him a heavy blow in the face, so that Jones needed treatment in the Haywood Hospital. It was reported, by the way, that several men were smoking pipes or twist tobacco on the bus, leading to a "fuggy" atmosphere.

People smoked in theatres, and though it was contrary to the regulations of the Theatre Royal in Hanley, it was nevertheless reported in 1860 that Mr. Rogers, the lessee, had frequently cautioned several patrons for smoking. Some even threw burning pieces of paper around, thereby putting other people - and the building - at risk. Rogers rightly saw this as a dangerous practice and a discomfort to his well-behaved customers.

Over the years, there has been plenty of evidence that tobacco is bad for your health. In 1867, Mr. Sneyd, the High Street grocer, was drinking with friends at the King's Head pub in Stoke. He put a fairly large amount of chewing tobacco into his mouth. Within a few minutes, he became insensible and fell, reportedly having swallowed a portion of it. He later died - "poisoned by tobacco" according to a press report.

Lastly, some people went to extraordinary lengths for their tobacco fix - or should that be heights?

In 1870, one chap climbed fifteen feet in the air for his.

Samuel Cronlan, a drunken potter, who was found by a policeman at two in the morning at the top of a gas-lamp in St John's Square, Burslem.

He'd prised open the door of the lamp, having scrambling all the way up the lamp-post for a light for his pipe.

COCKFIGHTING AROUND STOKE

(For The Sentinel's The Way We Were, September 2, 2017)

Huntbach's book on Hanley informs us that the blind Duke of Devonshire was in the habit of travelling to the Cat Inn, Northwood, from Chatsworth, circa 1780, in order to watch the cock-fighting.

It's a reminder of the fondness for the sport evinced by the well-to-do.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the Shakespeare Hotel in Brunswick Street, Newcastle staged mains of cock-fighting at its purpose-built cock-pit, with assemblies of gentlemen from Staffordshire, Cheshire and Derbyshire supporting the events.

It was all taken very seriously, with money riding on the outcome of these bloody contests which saw the cocks having steel spurs attached to their legs.

The Sneyds organised cock fights at Keele Hall, whilst fighting cocks were bred by the Sutherlands on their Trentham estate, where a poulterer's house was built in 1836. Cocks were also trained there.

The sport was banned by Act of Parliament in 1849 but survived illegally for decades because detection was so difficult.

Most pubs had a skittle yard or cellar, offering punters suitable privacy, and the local constabulary was hard-pressed to completely eradicate the activity.

In 1865, Commissioners were informed that "cock fighting & other brutal sports" were still being organised in the Fenton district.

Some of the cock fights took place at loc pubs at 4 a.m. I've also found references to cock-fighting in Burslem and Fenton as late as 1884 and 1885 respectively.

The lengths that people went to in order to secure victory for their bird is mentioned in the newspaper report of the Burslem incident:

"The cocks fought till they bled and lost a good many feathers. Before the fight the elder defendant put cayenne and butter on her bird's comb and feathers, for the purpose of crippling the other cock's fighting powers."

Also in 1885, it was reported that Adam Eden, a Hanford miner, had been charged with ill-treating two cocks belonging to a fellow collier, Henry Hartley.

Hartley had been in the habit of turning the two cocks and other fowls into a field close to his house.

Eden, who was alleged to have set the two cocks on to each other on two occasions, was subsequently fined twenty-one shillings and costs, with the press reporting:

"One of the birds was much mangled, but it was alleged in defence that they were game cocks and given to a bellicose use of beak and claw."

Cock fighting had an appeal that transcended the class divide.

What's interesting is that lower-class people were often likened in manufacturers' newspapers to a barbaric sub-race for supporting cock fighting and other bloodsports.

Their social betters, however, in pursuing similar activities, were referred to as "the fancy" or "sporting noblemen."

Lest you're still in any doubt as to the long-lived appeal of cock-fighting, I'll add that as late as 1956, it was reported in the Newcastle Times newspaper that the cruel sport had been carried on in Chester. The headline ran:

"Trentham Woman Hid Under Hay in Raid on Cock Fighters - Allegation. Blood Spattered Cockpit Found, Prosecution Tells Chester Court."

The report carried special interest as the woman in question came from one of North Staffordshire's most distinguished families.

Cock fighting is not unheard of even now, thanks to the dark forces of society, but it should truly remain in the past.

On my own travels, I have come across a display case of cock spurs at Battle Museum in Sussex, and a purpose-built cock pit from Denbigh, on view at St Fagan's Museum in South Wales.

THE COVENTRY CO-OP CAMP IN RHYL

(For The Sentinel's The Way We Were, June 24, 2017)

How many readers recall cheap and cheerful holidays at the Coventry Co-op Camp in Rhyl? It was opened in 1929, and known to thousands of Stokies, as well as factory workers from Coventry during their shut-down week - hence the camp's nickname, "Coventry by the Sea."

There's a photograph in my family's archive of yours truly, sitting in a pedal car that had been hired on-site. Notable is the long grass in the field above the camp, definitely in need of a trim. You'd often find rabbit holes in these fields.

My family, who lived in Wolstanton, stayed at the camp during the Potters' Fortnight on several occasions in the 1960s, when it was still attracting around 250,000 visitors a year - this, despite the rusty, corrugated iron fencing that enclosed it.

The wooden chalets had bunk beds and ants in the chalets almost came as standard. It was the epitome of a self-catering holiday, and the cookers in the chalets were a tad battered. There was no water. It was secured from a tap by the shower block. You could hire a larger, concrete chalet, with running water, for a bit more money. You took your own linen on holiday with you. Dad used to send ours in a large metal trunk - which also contained a fortnight's worth of holiday clothing - to the camp in advance. He'd collect this on arrival and push the heavy trunk to our allotted chalet on a hand-cart.

One of the abiding pleasures of our family was to put a plate of breakfast left-overs on the grass outside our chalet and to watch the scraps being devoured by flocks of ravenous herring gulls. Sports days included sprints, wheelbarrow races and egg and spoon races. The "egg" teetering on your spoon was a pebble from the beach. An emcee used a megaphone to instruct the various competitors, one of whom was my mother, who was then a useful sprinter. Every Friday, there was a party in the large, wooden clubhouse at which sports day winners would go up to the stage to received their prizes.

I recall winning a plastic Diana F flash camera. These were launched in the early 1960s and often given away as gifts at fairs, but considering that not everyone had a camera in those days, it was quite a reward.

Nightly entertainment took place in the camp clubhouse, where campers played musical chairs to the strains of the Gay Gordons and March of the Mods.

Soft drinks, such as Fanta pop, could be bought from the serving hatch, but booze wasn't sold. People often went off-site for a drink, perhaps to the Winkups camp nearby.

Most of the entertainment on the camp was homespun, and there would be a weekly fancy dress contest. Your Mum would go and buy some crepe paper from the camp gift shop and concoct a costume for you, or make you a hat out of odds and ends. In the accompanying photograph, taken in 1969, I am attired as Henry Cooper, whilst my sisters Julie and Glenys appear as Wee Willie Winkie and Mrs Mopp respectively.

On one occasion, my sisters and I caught a large number of crabs from the beach nearby, and placed them in buckets of water inside a kitchen cabinet, overnight. The next morning, the family woke up to a surprise, because the crabs had scrambled out of their buckets and were crawling all over the kitchen floor.

These holidays were very basic, and by the time we could afford to stay at Pontin's camps in the 1970s, we thought we'd made it in life!

LLANDUDNO: NEAR STOKE!

(For The Sentinel's The Way We Were, September 23, 2017)

At the recent Heritage Open Days weekend, I ventured to the Wedgwood Memorial Institute in Burslem to support an Arnold Bennett Society event.

A screening of the 1952 film The Card starring Alec Guinness, Glynis Johns and Valerie Hobson was offered, and although most us had seen the movie before, here was a chance to enjoy it in company as well as to recall one of my favourite holiday resorts: Llandudno in North Wales.

The North Shore Beach is only 83 miles away and has long been an attraction for Stokies, so it's no surprise that it was featured in Bennett's 1911 novel, The Card.

If you've read the novel, Llandudno is where Denry Machin - the titular hero - sells Denry's Chocolate Remedy, a supposed cure for sea-sickness.

A concert on the pier is cancelled due to a severe storm that drives a Norwegian fishing boat towards the shore.

Denry manages to board the storm-tossed vessel, masquerading as a press reporter for the Staffordshire Sentinel.

The ship is wrecked, but Denry manages to turn the incident to his advantage - and the cover of the Staffordshire Sentinel for August 4th, 1902 runs with the story, "Bursley Man in Gallant Sea Rescue - by a Special Correspondent."

He then buys the damaged boat and turns it into a successful tourist attraction on Llandudno beach. Ex-crewmen act as guides and recount the shipwreck story to the public.

Llandudno as a holiday resort is faithfully depicted in The Card.

There are trips out to Snowdon and the Isle of Man, and there is a glimpse of Professor Codman's Punch and Judy kiosk, which begun operating in Llandudno in 1864.

This newspaper appears as the Signal in Bennett's novels, but is given its proper name in the film adaptation.

Llandudno has other connections with Stoke-on-Trent, for William Woodall - pottery manufacturer and MP for Burslem - was buried there in 1901.

It has also been a popular destination for Burslem History Club day-trips, especially when the Victorian weekend is in full swing - our accompanying picture shows Chairman Alan Massey and wife Linda joining in the fun.

For two or three years, I took part in an annual charity event involving a relay race from Wolstanton to Llandudno.

The runners in our squad would run a few miles, refresh themselves in our support vehicle and then go out again.

As one of the more experienced runners, I would usually clock up about eighteen miles en route, though there was one year when most of us looked weary towards the end, as our bus neared the Little Orme.

We runners were asked which of us was up for one last push - up the testing incline below the Little Orme, down the slope and finishing at the town end of the promenade.

Though suffering badly from a knee ligament problem, I couldn't resist the challenge of leading our footsore volunteers over the hill.

You have to understand that madness is in the DNA of the long-distance runner.

Once we were on to the magnificent promenade, it took my mind off my injury. One year, I even gave Gemma Whilding a piggy-back as we crossed the finishing line.

It never feels as if you are far away from home in Llandudno, because there's the Staffordshire Oatcake Range in Mostyn Street - a must for Stokie holiday-makers craving their oatcake "fix."

One correspondent on Tripadvisor lavishes praise on the owner:

"What a wonderful, kind character she is, even if she's from Middleport."

WOLSTANTON SHOPS

(For The Sentinel, July 16, 2016)

I grew up in the 1960s when there was a very vibrant shopping scene in Wolstanton, long before the days of hybrid checkouts and reminders of unexpected items in your bagging area.

You could buy almost anything in the High Street, where services were diverse, ranging from Cyril Bird's gentlemen's tailor and outfitter to a branch of Askey's, "the largest fish, game and poultry dealer in North Staffordshire."

The shop of John Birkin, electrical engineers specialising in kettles, radios and washers, etc., vied for the customer's attention with the likes of Mary Dowler's wool, nylon and general drapery shop and Gater and Son's footwear specialists.

S. J. Gibbs, the jeweller, traded at 117, High Street, which later went under the name of Going For A Song. I interviewed Sidney Gibbs' daughter, Mary Frost, in 2001, and she remembered his easy-going nature:

"Old ladies used to bring brooches in for him to mend, and he didn't normally charge them. He was very well known for going for little walks in Wolstanton. He'd leave notes on his door - 'back in five minutes' - and he'd normally go to Holdridge's cake shop to buy cakes, or to his friend, Mr Gater, the shoe shopkeeper.

"Although he loved practical jokes, he also had a strong moral sense and would often say, 'There's no such thing as can't.' Dad drove an Austin 8 from 1939 to about 1953 and he always parked it at the top of Russell Street, near Truman's."

Some folk may remember Angela Hickman's hairdressing shop at 159, High Street, but better-known was the Dorimar Salon, which upon opening in 1961 was advertising "the latest in rinses and permanent waving." Its name, by the way, was a contraction of the names Doris (Hurst) and Marjorie (Mobberley), who launched the premises. Doris Hurst owned the salon for 39 years, retiring in 2000.

In 2014, Susan Dobson of Wolstanton told The Way We Were that she had worked at Dorimar in the 1960s. She recalled that her colleague, Jane, had a very special job - every Friday she would jump in her mini car and fetch fish and chips from the chippy in May Bank.

Another major High Street name for decades was Wallbank's the butcher. Many Wolstantonians recollect the family's shop, and when I interviewed Margaret Martin in 2001, she told me:

"Wallbank's had an abattoir attached. The butcher would go to Newcastle market every Monday and buy sheep or one or two cows. He'd bring them back and place them in a field at the rear of the shop, until he was ready to slaughter them. You could often see the sheep, beyond the gate, as you walked past the top of Grosvenor Place. Sheep in the middle of Wolstanton seems a strange idea, now."

Donald Walter Wallbank died in 2006, aged 80, and his Sentinel obituary recorded that he served Newcastle as a councillor between 1961 and 1970 and was closely associated with the planning of the A500.

I'm fortunate to have in my archive a shopping receipt for October 21st, 1960 that shows the prices of a few staple items of shopping bought from Holland's store at 129, High Street. The store, which offered grocery, bread, confectionery and wines and spirits, was then selling four pounds of sugar for two shillings and ninepence, a pound of mixed biscuits for two shillings and fourpence, half a pound of smoked bacon for two shillings and a pound of onions for sixpence.

My question is, though, could you get cash back?

WRITING LOCAL HISTORY

(For North Staffordshire Historians' Guild Newsletter, June, 2016)

The North Staffordshire Historians' Guild has debated the matter of how best to write satisfying local history for years, but we could easily extend the question by asking what do audiences demand of local history speakers?

There may very well be a correlation between what audiences demand of writers and what they require of speakers; but on the basis that no two audiences are the same, how do you pitch a talk - especially to a new audience - and how much must a speaker be prepared to adapt his content, tone and delivery in order to please those people who are paying him the privilege of listening to him? By the by, what is the difference between a talk and a lecture? I used to feel that I knew the answer to this one, but the reason I ask is that I've witnessed some thought-provoking, well-constructed, and yes, entertaining "talks" as well as some badly-prepared, stiff and windy "lectures" from speakers with no apparent empathy with their audience.

I've been a member of Burslem History Club for the past sixteen years, and have been Speaker Secretary for the last two. The whole, joyous experience has reinforced what I hope is my broad-minded and supportive stance towards speakers. After all, public speaking requires courage, concentration and command of one's material.

If you asked me what audiences really want from a speaker, I would reply that after all these years of standing before audiences I still don't have all the answers. Older speakers have offered me their thoughts. Philip Leese suggested that "entertainment" is important. One of my favourite lady speakers, an academic who has lectured in America, holds that public speaking is "theatre." Some self-styled "serious" historians may argue that such dangerous and irresponsible views may lead us down the path towards the Disneyfication of history presentation. However, perhaps the problem is with serious historians rather than the wider public they purport to inform. In fact, it pays not to be too proprietary about one's product. Publishers of local history exercise much editorial control over their writers - sometimes exposing the latter to unjust criticism by so doing - whilst history speakers usually soon learn whether their material, the fruit of all their obsessions and neuroses, is actually what the audience wants.

My general rule of thumb with audiences is never to patronise. One recalls Tony Blair's address to the Womens' Institute's national conference in 2000 when he was slow-hand clapped for his condescending manner. I've learnt much from speaking to WI groups - but even more from speaking to history societies across North Staffordshire. You speak to one of these august groups, thinking that you need to be at the top of your game, rattling off painstakingly-researched stats and facts, glorious nuggets of information - and then you find that some in the audience are nodding off.

It may be hard for some of us to accept, but presenting history in print or through talks is about forming a relationship with one's audience. It's about them, not us. You may well have blindingly-good research skills, impeccable sources and a scientist's precision in dissecting your assembled material - but if you lack the skills to convey your knowledge to a wider audience, and if you cannot give it meaning - then what's the point?

LONGTON PARK

(For The Sentinel, May 15, 2016)

There are many reasons for the abiding appeal of Longton Park, the most aristocratic municipal park project of the late Victorian period.

However, in trawling through the archives recently, I was interested to chance upon a report of Whit Monday celebrations in The Sentinel of 1917. It claimed: "There was more people in Longton Park than in Hanley Park, partly because the Longton Park is looked upon by people in other towns as being 'in the country.'"

Over the years, many events and attractions have inveigled patrons to the delightful park, whose grand opening in 1888 owed much to the enterprise of the Duke of Sutherland and civic leader John Aynsley. The park bandstand regularly accommodated musical ensembles, such as the Hanley Mission Band, the Fenton Orchestral Band, the Hanley Town Band, the North Staffordshire Railway Military Band and the Foden's Motor Works Band.

Occasionally, special attractions turned up in Longton Park, such as the captured German guns that appeared in February, 1919.

However, for those with an eye for the spectacular, the park didn't disappoint. Upon the unveiling of the Sutherland-Aynsley clock tower in 1892, the renowned equilibrist, Blondin - always a great draw with Potteries audiences - went through some death-defying tricks on the tight-rope. The antics of "the old man" - as he was described in the press - were marvellous for "one nearly three score years of age."

Early aviators also came to Longton Park, attracting rubber-neckers from far and wide. On the Whit Monday of the Longton Park fete of 1910, Captain Spencer attempted to take to the skies in a gas-fuelled airship, complete with two propellors. Crowds gathered in anticipation of the ascent of the cylinder-shaped contraption, but notwithstanding the great buzzing of propellors, it failed to get off the ground. The disappointment of the crowds was one thing; but Spencer then had to deflate his balloon, and "the odour of the escaping gas penetrated every corner of the Park."

It was evident that there was still much to be learnt about flying machines. A "local expert" who was watching that day observed that there was insufficient gas in the balloon for it to take off, and that had it got off the ground, it would have drifted pathetically along the ground to the park's clock tower before conking out. However, Spencer was also booked to appear on the Tuesday of the fete, and on that occasion he at least managed lift-off.

In ascending, the underside of his cabin grazed the protective cordon separating him from his audience, and the onlookers ducked as one in consequence. The airborne craft then twisted around several times like a spinning top as Spencer tried to keep its nose to the wind. After a decidedly bumpy ride, the airship eventually descended in a clover field in Oswestry some three and a half hours later, Spencer having long given up his attempt to touch down again in Longton Park.

Magnificent men in their flying machines continued to make visits to Longton Park. Such a man was Gustav Hamel, a pioneer aviator who had already established a reputation for himself prior to his appearance at the Longton Park fete of 1913, where he flew his Bleriot monoplane over the park.

Longton Park today must surely be the city's most beautiful municipal park, and on the evidence of my most recent visit, I might have to record that it is the friendliest. And as a bonus, it no longer stinks of hot air balloon gas.

LONGTON AND ATHLETICS

(For The Sentinel, March 19, 2016)

I've lost count of the number of times I've sped through Longton in either the Potteries Marathon, or its little sister, the 'Arf. Crowd support was always vociferous in that neck of the woods, but then again, athletics in Longton has a variegated and quirky history.

Though a capable runner, I never took it quite as seriously as some foot-racers did in 19th century Longton. This sport took place over a pre-arranged distance, sometimes in local streets, or in the country. It drew huge working-class audiences, especially when money was wagered on the races between bullet-fast lads from the pit or potbank.

However, foot-racing was such a competitive business in Longton that many wing-heeled runners began to consider the aerodynamics of the sport - with shocking consequences for the general public. In 1840, William Yates and George Halford, ran against each other on the Stone Road, near Longton, attracting a "riotous multitude." Yates was stripped, almost naked, much to the annoyance of magistrate T. B. Rose who harrumphed that he had no objection to young people running in proper places, but to do so, divested of clothing, in the main highway, was a different matter.

After foot-racer Adam Bough had indecently exposed his person on a public road between Longton and Fenton in 1853, Rose referred to the practice of foot-racing, "not only by boys, but grown-up men, in a state of nudity," being very common, and a nuisance to passers-by. Another 1853 case referred to nude foot-races being "prevalent in the neighbourhood of Longton" - and though I've found references to racing au naturel elsewhere in North Staffordshire, Longton does seem to have been particularly infamous for it.

Running in the buff was an even greater moral outrage when athletes chose to do it on Sundays. The police courts reported in 1856 that four lads were running races in Furnace Road in a state of semi-nudity. They did so on the Sabbath - "just at a time when people were returning from church," according to the local press.

One particular court case regarding nude Sunday racing on the public road at Normacot, in 1866, saw magistrate J. E. Davis showing altogether more latitude than his fellow legislator, the spiky T. B. Rose. Davis accepted that young boys at this time usually worked for five and a half days per week. Sunday may well have been an inappropriate day for their activity, but there was precious little other time. He gently reprimanded that racing was a nice sport, but it ought to be done at the proper time and place. "The boys must take care," he chided, "not to bring their mothers into trouble again."

Eventually, athletics became more respectable, and in the 1880s, the Congress Football and Athletic Club regularly convened at the Congress pub in Sutherland Road in order to organise hare and hounds activities. In essence, these were cross-country chases, and they covered many a mile. One run, in 1886, covered an area stretching to Sandford Hill, Adderley Green, Bentilee, Park Hall and Weston Coyney, before returning to the Congress pub. All those completing the course would surely have welcomed a post-race potation.

Finally, here's a story concerning a lost pub of Longton, the New Town Hotel, which stood in Uttoxeter Road. Renowned female pedestrian Madame Richards undertook to walk a thousand miles in a thousand hours in the grounds of landlord Swift's pub, in 1874. Though it was a distance she had completed before, it seems from a report in the press that she struggled to repeat it on account of the "gambling and dog-running" also going on in the grounds.

Such was the rough-and-ready nature of working-class recreation in Longton!

KEMBALL COLLIERY

(For The Sentinel, February 27, 2016)

There are few areas in the country that have a prouder mining history than Stoke-on-Trent - which could also boast of a notable first in November, 1943. In that month, the Kemball Pit, belonging to the Stafford Coal and Iron Company at Great Fenton, was opened as the first pit training school in Britain.

It will be seen that on this occasion - four years before Nationalisation of the coal mining industry - North Staffordshire was ahead of the game. The Ministry of Fuel and Power had decided that underground training centres would be established across the country's coalfields, but local pit owners, trade union officials and the local education authority combined to launch the first training pit at Fenton.

It was reported that Kemball Pit had not been worked for two years, but had been kept well ventilated. It now offered the chance for all newcomers to the mining industry to receive training before going underground to work with experienced pitmen.

We are reminded that back in 1943, men were being conscripted - at random - into employment in the mines in order to replace the thousands of miners who had received their wartime call-up papers. However, the point was made at the opening ceremony that the scheme at Fenton had not been triggered by the need for wartime "Bevin Boys" - those men who worked underground through the recruitment scheme of Ernest Bevin, the Minister of Labour and National Service.

Mr. Crofts, President of the North Staffordshire Colliery Owners' Association asserted that the training pit "was not of war-time growth and was not merely for wartime needs".

"It could take in, comfortably, all the additional youths and men so urgently required at present, and at the same time deal with the normal young recruits for whom it was originally intended."

The wider history of Kemball Colliery - sometimes known as Stafford No. 1 - is also worth mentioning, for it had operated as a pit from 1876 right up until November, 1963. However, the site was used for surface training until 1989. One National Coal Board document in my archive explains how school leavers set about joining the mining industry. They usually visited Kemball and an underground training district at a local colliery prior to leaving school.

If they then enrolled as mining trainees, they received a two week induction course into mining at Kemball, followed by a three-week course in mining theory and then another three weeks in an underground training centre at Florence, Hem Heath or Wolstanton pits. They then returned to Kemball for a month's basic engineering training in the workshops before going to their colliery of choice. Afterwards, they had twenty days close supervisory training on the surface, but they still had to return to Kemball for pre-coal face training and to undergo further training to qualify them for coal face work.

We can see from this how intensive a young man's mining training was, and how he was being prepared for not just a career, but a whole working life in the pits.

In addition, Kemball also organised induction and refresher courses for locomotive drivers, guards and shunters and provided training in such as crane driving and the handling of materials. The site embraced workshops, a locomotive garage and track and a fully equipped mock coal face. Former Port Vale FC Chairman Bill Bratt - a recent speaker at Burslem History Club - told us how he'd received his face training at Kemball, before working at the Chatterley Whitfield Colliery near Tunstall.

However, times change. A Holiday Inn now occupies part of the old Kemball Colliery site, whilst Kellingley Colliery in North Yorkshire, the last deep pit in Britain, closed in December.

THE WEDGWOOD INSTITUTE IN BURSLEM

(January 31, 2016)

The restoration of the Wedgwood Institute in Burslem - courtesy of the Prince's Regeneration Trust - constitutes a phenomenal boost for the much-maligned Mother Town, and for all of us who have waxed rhapsodic over the majesty of its sumptuous façade.

I'm one of many members of Burslem History Club who have lavished praise upon its Venetian Gothic frontage, and at the time of writing, I am two weeks away from delivering my second lecture in less than three years on the history of the institute - this time, for the Workers' Education Association.

Describing the façade is well-trodden ground for historians. However, the whole tortuous history of the building offers up many points for discussion. Why on earth did the project take so long from conception to completion, and what do the delays tell us about the pre-Federation mindset of local people? Was the project the fanciful desire of the relatively few - mere civic grandstanding - or was all of Burslem behind this ambitious plan to commemorate its most famous son, the illustrious Wedgwood?

It's a fascinating story, well deserving of lecture or book treatment, but for the sake of this short article, let's confine ourselves to a few observations as to how the institute was used.

Information contained in the Burslem Board of Health reports, local newspapers and other documents tell us much about how the new amenity functioned. The public reading room and library were opened in October, 1869 and October, 1870, respectively. The library offered all the works of Charles Dickens, whose popularity knew no bounds both before and after his death in 1870. It was stated in 1871 that a volume of Dickens was rarely in the library for an hour. The library had strict rules, based on the model of libraries in larger towns. All newspapers and books had to be vetted by the committee prior to being made available in the reading room, indicating one aspect of the social engineering that was in evidence at the time.

The Burslem Board of Health Annual Report for the year ending September 25th, 1871 reveals much about those members of the public who used the library and the subjects that interested them. Of a total of 644 ticket-holders, comprised of 550 men and 94 women, 87 were pressers or cup makers, 63 were engravers, modellers or gilders and 56 were warehousemen and lodgemen. The whole list embraces a healthy spectrum of potters, pen-pushers and the upwardly mobile. Over roughly the same period, fiction proved to be hugely popular, with 7,894 issues, with history and biography being the most enticing non-fiction category, with 1,833 issues.

All of this was an indication of the change in working class tastes in the second half of the 19th century, and the rise of more rational pastimes. Educational or intellectually-stimulating activities were provided for working people as an alternative to the public house. However, if the makers and shapers of mid 19th century Burslem desired a more rational society, they were nevertheless suspicious of the radical elements that came with it.

The Potter's Examiner newspaper - subtitled "the Workmen's Advocate" - announced in 1869 that accommodation for trade societies was now available in the multi-roomed Wedgwood Institute, whose committee was willing to cater for the unions at a rent comparable to that being paid to the pubs in which they customarily met. We would ponder this today, and conclude that here was a fine chance for the moral champions of Burslem to break the link between the working man's political meetings and the demon drink. However, the newspaper report evidently ruffled a few feathers among the institute's committee members, who subsequently attempted to distance themselves from some of the comments in the article.

The committee minutes for 16/9/1869 record that the chairman and Mr. William Woodall DENIED that they had gone so far as to express "their willingness to accommodate trade societies." They had only agreed to recommend such use to the committee if it were considered "expedient". There was concern among committee members that their neutrality might be questioned if they were to permit certain groups to meet at the institute.

The question of social control within a building that was intended to enlighten working people was one that exercised the minds of the committee. In October, 1869, it was reported that the reading room had been well-attended but that the large number of youths had not been conducive to maintaining order at all times. During one evening, 150 youths had crammed into the lecture theatre and were provided with illustrated newspapers, indicating that there was a need to make special provision for them.

The popularity of the reading room was not always conducive to study, as some people just couldn't stay quiet. Various references in the local press and the committee minute book refer to the difficulty in imposing silence in the reading room. The anti-social behaviour of one visitor was particularly abhorrent in 1874. The Cobridge manufacturer, Elijah Chetwynd, who often fell foul of the police courts for his drunken behaviour, was found drunk in the ladies' class room of the institute by the hall keeper, Thomas Baddeley. He was also charged with assaulting one of the young ladies. A police constable was fetched, and meanwhile, a large group of people assembled outside the building, to rubberneck at the proceedings. The constable allowed some of Chetwynd's friends to take him home safely, but in the subsequent court hearing, the stipendiary, who was by now tired of seeing this old offender, sentenced Chetwynd to fourteen days in prison.

The archives and the fruits of my own research yield an abundance of information in regard to how else the institute was used by the public. It's a narrative that offers up famous names like Arnold Bennett and Oliver Lodge. The wider history of the institute is variegated and thought-provoking, revealing much about how little the disposition and outlook of Potteries people has changed since the mid 19th century.

At a time when we are grateful that the Wedgwood Institute will be fully restored and brought back into use, we may well choose to re-read the prophetic words of James Edwards, a town dignitary who was speaking in January, 1859. He reasoned:

"It would be a very poor compliment to Wedgwood to erect an institution which would afterwards fall into decay and disuse, and become a stigma to the neighbourhood."

Yet in our brave new world of the early 21st century, this was exactly what happened, when the Burslem library closed, and English Heritage listed the institute as one of the top ten most endangered Victorian buildings in 2010. All of us who record and value Burslem's history can be relieved and thankful that a new, exciting stage in the building's history is just around the corner.

HARTSHILL AND THE MINTON FAMILY

(For The Sentinel, November 14, 2015)

They say that if you really want to understand and appreciate buildings, you should always look up.

However, only a fortnight ago, I could be found wandering around the Houses of Parliament casting my eyes in the opposite direction.

As I stood admiring the magnificent Minton floor tiles I smiled and considered the lasting legacy of one of our greatest master potters.

Herbert Minton himself purchased Longfield Cottage in Hartshill in 1819, a property described by the historian Simeon Shaw in 1829 as a "very beautiful and compact cottage residence" rising above the industrial smoke of Stoke and in an area that was only thinly-scattered with homes.

Minton's domicile stood opposite the still-extant Noah's Ark pub and was later rebuilt and extended as his family grew. He also bought the neighbouring Longfield House in 1836.

The development of Hartshill from the mid nineteenth century owed much to the influence of the Minton family, and in particular, Herbert, who was the son of the Stoke pottery manufacturer Thomas Minton.

History is replete with stories of weak and vacillating sons who were unable to build on the enterprise of their fathers. This is not one of those stories.

He developed several profitable partnerships and established conspicuous manufactories in Stoke with the result that Minton ware won medals at the Great Exhibition in London (1851) at New York in 1853 and Paris in 1855.

The firm's encaustic floor tiles came to be used in other buildings I have admired on my history travels, ranging from Lichfield Cathedral to the Bartons Arms pub in Birmingham.

Minton certainly left his mark in Hartshill, where his surviving buildings constitute a feast for the eye.

Holy Trinity church, founded by him in 1842, boasts an elegant, tapering steeple that seems to prick the lower clouds, whilst the old Church School, the Minton Cottages - built for his more valued workers - and the former Hartshill Working Men's Institute are further evidence of the guiding hand of a man determined to leave his stamp on the village.

Minton retired to Torquay in 1855 and died there in 1858. Appropriately, he is buried beneath the chancel of Hartshill church.

Other members of the family - notably Herbert's nephew, Colin Minton Campbell, who died in 1885 - continued to wield an influence in Hartshill and Stoke.

In 1880, another family member by the name of Herbert Minton opened what was designated the King's Croft Cocoa House in Stoke Lane.

It was stated in the local press that this was a densely-populated district, most of the houses being occupied by the labouring classes.

The new amenity can be seen very much as an attempt at social engineering by the Minton family, for the new premises sold cocoa, coffee and tea, and a few edibles, but no alcohol.

One room contained a piano and offered draughts and dominoes. The interior evidently aped that of a beerhouse or pub, as there were tasteful pictures on the walls.

It was reported that "The people seem to appreciate the efforts of Mr Herbert Minton to decrease the great amount of drunkenness prevalent in the Pottery district."

However, even the all-powerful Minton family had to genuflect to the abiding attraction of booze.

The cocoa house didn't survive, whereas several local watering-holes, including the Jolly Potters and the Robin Hood did.

Just for good measure, the former Church of England School - now styled the Minton Centre - plays host every year to the Minton Real Ale Festival.

Whatever would the Minton family have made of that?

UP THE VALE!

(For the GMB website, 2015)

The sponsorship deal linking the GMB trade union to Port Vale FC in Stoke-on-Trent continues to benefit both parties - and besides, it's a wholly appropriate partnership when you consider the early days of this homely little football club.

Vale's community role in the distant past can be explored through a look at our local newspapers over the years. Information I have harvested underlines the close relationship with the club and its working-class support in Burslem.

James Mason was once a Vale player, who went on to become an international referee. His reminiscences were recorded in the Newcastle Times newspaper in 1944, and he remembered that when Vale played at Westport in the early 1880s, the players changed at the still-extant Travellers Rest pub in Dale Hall, and then walked to the ground. Upon moving to their next ground, in Moorland Road, they changed at the New Inn in Market Place, Burslem, from where they also walked to their headquarters. It wasn't until a little later that these working-class lads were driven to their ground.

The club has existed on the edge of Burslem town centre for much of its history, so it is no surprise that it has had close connections with the wider community - and charitable causes - in Burslem. There are several historical connections between the club and the Town Hall.

In the 1880s, there were treats to the "ragged children" and the poor of Burslem, who were amused by Port Vale FC in the Town Hall. Hundreds of children sat down to a free tea as entertainment - some of it provided by club members who sang Who killed Cock Robin. It is difficult to imagine present-day Vale stars entertaining the public from a stage, but in 1887, one of the players, Billy Poulson, recited The Patent Hair-brushing Machine. By the way, fans of Arnold Bennett will remember that this was given as one of the entertainments at the free and easy at the Dragon Hotel in Clayhanger.

The club's annual dinner often took place at the Town Hall and this was an opportunity for various speakers and club officials to assess the progress of the players and club. At the 1886 function, it was claimed that there was no better goalkeeper in England than Vale's number 1, Hanley-born Billy Rowley. He was sold to Stoke, and won two caps for England. Gatherings such as this would be concluded with songs and recitations.

Port Vale-orientated meetings have been convened at numerous venues in Burslem since the club was formed, and in recent years, the Supporters' Club has held meetings at the Leopard. In the late 19th century, The Leopard Hotel in Burslem originally occupied numbers 19-21 Market Place.

A few doors away, at number 26, was the Burslem Coffee House, aka the Borough Arms. It opened in 1879 and was run on temperance principles, being offered as an alternative to the plethora of drinking establishments in the town. It was aimed at working men. Vale often held meetings at the Coffee House, and it is evident that one club member at least was happy with the arrangement. J. Brindley was a temperance advocate, and at the club's annual meeting in 1885, he told fellow members that he had been averse to attending Vale matches at Mr. Bew's ground (in Moorland Road), Mr. Bew being a publican. The informal gatherings at the Coffee House were evidently agreeable occasions, with music being provided. There is a reference to the Port Vale Prize Band giving selections from the opera Maritana at the venue in 1888.

One local lad who made good is darts legend Phil Taylor, who made the throwaway remark in recent years that he thinks he is a better singer than fellow Vale fan Robbie Williams. Phil is one of a number of celebrities who helped to make a modern recording of The Port Vale War Cry. This is a supporters' song that was composed by Fred Glen in 1920.

It was launched at a club smoking concert at the Albion Hotel in Hanley, with the supporters' club chairman, the Rev. A. Hurst, beseeching the club members to "Sing it to your wives and children, Sing it on the ground and in the streets, and make yourself perfect nuisances with it." Incidentally, in the first match after the song had been launched, Vale beat Hull City 4-0, so there was an immediate impact!

VALENTINES DAY

(For The Sentinel, February 14th, 2015)

It's St Valentine's Day again, a day that reminds us of how wonderful - or how embarrassing - love can be.

Embarrassing? Well, in 1964, a major traffic jam was caused in Brazil when a couple kissed in a car and their dentures became inextricably locked together.

But let's come home for a few stories about the complexities of amorous engagement.

These days, relationship break-ups and marital infidelity are rarely secrets for very long, due to the wonders of social networking - but as we all know, "the past is a foreign country. They do things differently there."

Take Silverdale in 1859. Several cases were brought before the magistrates relating to the practice of burning effigies of married men and women suspected of infidelity. A number of youths were cautioned, and a couple of the suspected ringleaders were women.

A similar case was reported on the Staffordshire/ Cheshire border in 1874, headlined, "The Mow Cop way of suppressing adultery." For some time, there had been rumours in the village concerning the alleged intimacy of Thomas Bossons, a forgeman, and a married woman, Mrs Booth. The local gossips, seeking to draw attention to the alleged infidelity, made effigies of the suspected guilty parties, carrying them around the village. Talk about embarrassment! It was reported that the whole village turned out, the procession stopping at Bossons' house where some stump oratory was indulged in regarding the sinfulness of adultery. The ringleaders hoped that this public admonishment would bring an end to the carryings-on between Bossons and the married woman. The effigies were then carried past the house of Mrs Booth, where a similar denunciation was made, before the villagers found a place to dispose of the effigies. Placing them in an indecent position, they set fire to them, the crowd roaring their approval.

Today's social networking often shows that much malicious opinion is based on a modicum of fact - as was the case in Mow Cop, it seems. The matter went to court, the magistrates ruling that the disorderly demonstration was a disgrace, even if there were grounds for the rumours referred to. "In the present case, however, there appeared to be no such grounds, and therefore their conduct was doubly disgraceful."

The nineteenth century court reports detail many cases of marital strife. There sometimes comes a time in a man's life when he has to bury his wife. Unfortunately, one Chesterton miner tried to do this whilst she was still alive. The local press reported in 1884 that "Mad Jack" Rowley - being not very sensible even when sober - got drunk and dug a hole in his garden, subsequently pushing his wife into it. When Mrs Rowley refused to lie down quietly, he struck her over the head with his spade. The local newspaper that reported this story quite rightly made the point that the magistrates, in only charging Jack for being drunk and disorderly - and fining him ten shillings and costs - had let him off lightly. "Either the Newcastle magistrates or the police have blundered," it declared.

To end on a more amusing note, how has marital bliss been seen through product advertising over the years? For all of you wishing to have the key to a happy marriage, I refer you to an illustrated advert on the front cover of The Sentinel, in 1901. This depicts a well-dressed man and his wife sitting together on a sofa by their living room window, the woman lovingly resting her head on the shoulder of the husband, who is calmly smoking a cigarette. The caption runs: "How to be happy, though married. The husband smokes Ogden's Guinea Gold cigarettes and the wife thinks them delightful."

You see, marital harmony really is that simple!

WORKING ON A 19th CENTURY POTBANK

(For The Sentinel, February 7th, 2015)

What was it like working on a potbank in the nineteenth century? For an answer to that, we might pay a visit to the Gladstone Pottery Museum in Longton, or we might conduct our own research, trawling through contemporary newspapers and archive material.

What I find thoroughly intriguing is that then, as now, capitalists were far more adept at self-promotion - and indeed, were given ample opportunity by the press - than working people were at highlighting their own points of view. When we read in the 19th century newspapers of the great deeds of master potters like Enoch Wood and the public dinners that were regularly held in their honour, we naturally question what it was like to work for these captains of industry - and whether to believe everything that was written about them in the press.

Potbank workshops and yards may have been functional, but the facades of manufactories were often magnificent. The frontage of Samuel Alcock and Company in Liverpool Road, Burslem, was a good example, being added in 1839 by Shelton architect Thomas Stanley. Dominated by an elegant Venetian window, the new factory façade was described by historian John Ward as "the most striking and ornamental object of its kind within the precincts of the borough." On the day that the first stone of this beautiful new façade was laid, in April, 1839, a thousand people, including the personal friends of Samuel Alcock and hundreds of employees, assembled in Liverpool Road, no doubt jostling for a decent view of proceedings. Several speeches were made, including one by Mr. Francis Emery, one of the company's bailiffs. He opined that the workers "really valued, and he trusted, appreciated, the benefits they were deriving from the liberal, spirited, and comprehensive manner, in which their business had long been and was conducted. Of that system they were every day feeling the benefit." He claimed to be echoing the sentiments "of all the workmen who heard him". However, the tub-thumping, back-slapping nature of this ceremony represents only one image of the operations of Alcock's manufactory at this time.

We are reminded that Alcock's is believed to have been the factory that Charles Shaw joined as a cup-handler at the age of eight. Shaw's recollections were first published in The Staffordshire Sentinel in the 1890s before appearing in book form in 1903. In it, he refers to the multitude of sins being committed behind the imperious frontage of this busy enterprise, which exported to America. In his autobiographical When I Was A Child, Shaw writes about the "jollification and devilry unnameable" which accompanied the drinking that was done on the potbank. The men would smuggle beer into the workshops, and young women would be persuaded to join in the indulgence. Sometimes, drink was forced upon them, and they rapidly became intoxicated. The men would then scheme to stay in the workshops overnight, and the drunken women were taken advantage of in the most lustful, bestial manner. Shaw suggests that the factory owners and their foremen probably did not know about these orgies, but that the factory watchman was bribed so that he would say nothing.

Alcock's factory is long gone, but GMB trades union official Duncan Carson, aged 47, believes we can learn something from the conflicting accounts of its history: "Several colleagues of mine formerly worked in the pottery industry," he declares. "It's a fact that that the development of trades unions made potters' working conditions infinitely more comfortable than those endured by Charles Shaw."

When I remind Duncan that Shaw died in poverty in 1906, he observes: "Then his autobiography is all the more poignant - and relevant as a document that highlights working class struggles of the 19th century."

REMEMBERING FANNY DEAKIN (1883-1968)

(For the GMB website, January, 2015)

The politicians I most admire are those that don't give two hoots about toeing the party line if there is a battle to be won. Independent spirits, chancers and mavericks who are prepared to be unorthodox in supporting a deserving political cause.

Some of these folk are often variously derided as enfants terribles, raving firebrands, single-issue zealots, protest politicians or bilge-spouting fruitcakes.

You'll find such loose cannon in every political party, rubbing people up the wrong way here and putting their feet in it there. However, I reckon that good intention doesn't always present itself to us wrapped up in silk ribbons and sprinkled with lavender water.

Fanny Deakin of Silverdale, near Newcastle-under-Lyme, North Staffordshire, was one of the area's most memorable politicians. I am too young to have known her, and I suspect I may not have liked her - but that wouldn't have dissuaded her from fighting for me if she believed in my cause.

Fanny Deakin was born Fanny Davenport in Silverdale in 1883 and lived all her life in the village. She spent much of her childhood on Spout House Farm, kept by her father. She seems to have been a rebel from an early age, as was noted by her Dad.

In 1901, Fanny married Noah Deakin, a local collier. Shortly after, their first child, James, was born, though he only lived a few weeks. In 1903, their second son arrived, and he was named Noah after his father - he was their only child to survive into adulthood.

Noah senior, like many Kent's Lane Colliery miners at this time, suffered dreadful conditions underground. What made things worse is that the coal owners decided to make their employees work their shifts - nine hours - without a break. This triggered the so-called snapping-time strikes of 1910 and 1911. The men argued for a twenty-minute break and there were disputes. Fanny doesn't appear to have been actively involved in the dispute, but with her husband being a miner, she was inevitably on their side.

During the 1926 General Strike, she was actively involved in campaigning for the miners, as was her son, Noah. They distributed a miners' newspaper called The Wedge and they fly-posted propaganda material round the local collieries, pasting leaflets on colliery windows, walls and wagons. She recorded in her notebook that on average, she walked twenty miles a day at this time in order to meet miners' leaders in distant pit villages such as Smallthorne and Norton. She didn't have transport, and was lucky if she could cadge a lift. She came to be recognised as the accepted leader of the mining community, which was remarkable for a woman in 1926. She led processions and is remembered as one of the speakers at a huge gathering on Wolstanton Marsh during that year.

It's no wonder that she was sympathetic to the cause of the miners. In 1931, her husband Noah was involved in an horrendous accident at the Fair Lady Pit in Leycett. By the time he was discharged from hospital, he had lost his sense of balance and struggled to walk even with a stick. For much of the time, he was confined to bed, and never worked again. He received a meagre sum in compensation from the colliery, and so Fanny had to fight the colliery for better terms. She eventually got them, but their standard of living fell dramatically.

Fanny had become involved in local politics in 1917, but in 1923 she became the first woman ever to be elected to the Wolstanton Urban District Council, which in those days embraced Silverdale.

In terms of party politics, Fanny had been a member of the local Labour Party in Silverdale, but she became a member of the Communist Party around 1925. She remained so for the rest of her days, and it did not have an adverse effect on her support in Silverdale. People voted for her as a person and for what she did for them, not for her politics. Letters from Russia, addressed to "Red Fanny" were often received in Silverdale. There was a big Communist meeting at the Victoria Hall, Hanley, in 1928, and Fanny was in the chair. She twice joined trades union delegations on visits to Russia.

She also campaigned for better maternity care for women and free milk for babies - indeed, these had been her primary aims when she had first entered politics. She was part of a deputation of working people who met prime minister Ramsey MacDonald at Downing Street, in 1931, and she petitioned him for one pint of milk a day for pregnant mothers and free milk for children up to five years. She succeeded. She also successfully campaigned for local clinics. However, the pinnacle of her achievements was the establishment of a maternity home at Chesterton in a large house at Farcroft. The maternity home opened in 1947, and bore her name. At the time, she was Chairman of the Maternity and Welfare Committee in Newcastle.

I've only covered a few bullet-points in her variegated political life. But how is she remembered? Even today, Fanny still divides opinion in Silverdale whenever her name is mentioned. Some people did not like her politics, and others didn't approve of the fact that she was sharp-tongued and called a spade a spade. Some folk were brought up to walk on the other side of the road when passing her front door. However, to other people, she was a bigger Christian than many church-goers because if she could help anybody, she would. She'd fetch the doctor for people, or deal with the police - though sometimes, she'd be exasperated by the inability of people to stand up for themselves, and would say to them, "Kick, you buggers, kick!"

She was remembered in 1991 when a play entitled Go See Fanny Deakin was held by the Silverdale Community Play Association at Knutton Recreation Centre. This was planned and staged by local people and I went to see it. It was one of the most vibrant theatrical experiences I have ever seen, and fitting tribute to Red Fanny!

ENTERTAINMENT AT BURSLEM PARK

(For the Burslem History Club website, 2014)

Burslem's 22-acre municipal park opened in 1894. Much has been written about how Burslem Council, in reclaiming industry-ravaged land, effectively turned a sow's ear into a silk purse. In creating order from the chaos of old cinder heaps, abandoned colliery workings and rough farmland, the local authority did a sterling job that has stood the test of time, notwithstanding all manner of geological and environmental challenges.

But how has the park entertained visitors over the years? To find out, we can consult the parks committee minutes - an invaluable source of information - or we can trawl through local newspapers. We might consider the view of Arnold Bennett, who wrote about how patrons of the park used it in the 19th century. Anna of the Five Towns (published in 1902) is particularly revealing about Bennett's angle on the park as a municipal amenity.

The facility was certainly an appropriate stage for multifarious events that raised money for the park or for charitable causes. These included the Burslem Horticultural Fetes, which not only constituted a celebration of green-fingered skill, but also offered more general entertainment in the form of Pat Collins' fair and various sideshows. Also popular was the Burslem Park Carnival, which came to incorporate the Haywood Hospital Queen competition. The cream of female beauty from companies such as George Wade and Son, H. and R. Johnson and Burslem Co-op entered these contests.

Some structures in the park were specifically built to amuse the public, including the bandstand and the bowling greens.

The park aviary was first conceived in 1899, and a tender of William Cooke, amounting to £120 for the erection of the structure, was accepted in September, 1900. The aviary housed exotic or unusual birds such as Australian grass parrakeets, Virginian nightingales, and redpolls as well as a throstle and a barn owl.

One who saw the gradual decline of the aviary in the 1930s was Philip Oakes. In his excellent book, From Middle England: A Memory of the Thirties (1984), he wrote:

"A green-painted aviary overlooked the lake. It smelled of dusty radiators and bird droppings and comprised one long cage which contained several canaries and budgerigars, a sulphur-crested cockatoo and, for a short time, a toucan. One Sunday on our way to chapel I looked through the window and saw it lying dead on the floor. My uncle called at the park-keeper's lodge to report the casualty. 'I'm not surprised,' said the park-keeper. 'I caught some lads feeding it toffees yesterday.'"

In 1995, it was reported that the aviary had closed down after more than half of the birds had either been shot, stolen or released into the wild. It was consequently demolished.

In 1919, a new point of interest in the park was a captured German gun, displayed for all to see - and on the subject of War, the park really came into its own during the 1939-45 conflict.

Along with other Potteries parks, it staged Holidays At Home entertainments. These were not only a release from the cares of war, but were an attempt by the authorities to persuade pleasure-seekers to stay at home during the holiday period rather than to risk long journeys in what were unsettling times. During August of 1944, Burslem Park offered amusements such as a baby show, a rabbit show (it being the case that people were encouraged to eat rabbit meat during World War Two) and performances from the Home Guard Band and the Royal Marines Band.

In recent years, the Burslem Park Partnership has been in the vanguard of efforts to restore the park and to provided entertainments and facilities for the 21st century.

I've even helped to provide amusement in Burslem Park myself, for in the Burslem Festival Bank Holiday procession of 2001 - which began at Burslem Park - I appeared as one of the costumed characters. If you must know, I was the one dressed as a banana.

WHY JOIN BURSLEM HISTORY CLUB?

(For the Burslem History Club website, 2013)

Have you ever had a friend tell you that you MUST read a certain novel, or go and watch a particular play - and when you do, you've been singularly underwhelmed? Well, this is one of the reasons I prefer not to make hectoring recommendations about anything - even about Burslem History Club.

So let's just say that what follows is a celebration of aspects of club activity that have given me pleasure over the thirteen-plus years I have been involved. I'm being purely subjective, extremely nostalgic, but above all, very grateful for some wonderful times. If in writing the following ruminations, I persuade you, dear reader, to give the club a try, then so much the better.

It's a club that is only as strong as the bonds of friendship and mutual respect that underpin it. In this sense, "club" describes us far better than "society" ever could. Our monthly get-together sees an inevitable focus on whosoever is addressing the audience that night - and we've enjoyed no end of silver-tongued, authoritative speakers who have charmed, amused and informed in equal measure.

However, it is the camaraderie - and to put it simply, the fun - of the evenings that keep people coming. Bob Adams is a long-serving member, and can always be relied upon for a well-timed wisecrack if our evenings are flagging. Like many seasoned Boslemites, he has a wealth of stories and a very visual memory. Here is Bob talking about his childhood:

"The other thing about growing up near to the Vale Park ground was that kids used to 'save cars' - in other words, there would be the threat to drivers that the tyres would be let down on their parked cars by the time they returned from the match, unless they gave kids a shilling. I lived in Gordon Street, and my patch was from Jackfield Street to Dartmouth Street. Other kids had different patches nearby. You'd write the car registration numbers down and if you were lucky the owners would give you some money when they came back after the match - especially if you'd got a duster and polish and cleaned it a bit. But one youth went over the top. One car on his patch had got some rust on it, and so he used sandpaper and a wire brush. He must have done about £200 of damage, scrubbing down to the bare metal!"

On the occasions when the club embarks on a day excursion, you discover what really makes people tick - or doesn't. We visited the Black Country Museum in 2008, and in a mad moment partly triggered by three pints of beer, three of us decided to have a go on the helter-skelter on the museum fairground. We climbed up the spiral staircase leading to the top, with our then-chairman, seventy-something Harold, leading the way. With great brio, he whizzed down on his mat. Being acrophobic, I just about kept my cool in order to tentatively descend at about half the speed managed by Harold. I was surprised to see our fifty-something friend Alan (now our vice-chairman) waiting for me. He'd been right behind me as we had ascended the staircase. What I hadn't known is that he has an aversion to anti-clockwise movement, and he had walked back down again.

The trips out - to destinations such as Bakewell, Liverpool, Stratford and York - have been special. Scrutinising the paintings at the Lowry Centre in Salford and visiting the nearby Imperial War Museum North did much to broaden the minds of some of us, though I couldn't help noticing on that visit that one particular club contingent had asked the coach driver to drop them off a local pub, where they stayed all day. Then again, what makes a memory? Eating cod and chips outside a chippy in sun-baked Llandudno, whilst watching the goats on top of the Great Orme took a bit of beating for me.

Personally, I relish every aspect of my involvement with Burslem History Club, and on the nights when we gather, it is very agreeable to be able to extend the evening with further drinks in the Leopard, the Duke William or the Bull's Head. The nights are so much fun that perhaps I really should be bullying people into joining us. Come to think of it, I'll be banging on your front door tomorrow!

CHURCH HAS TOWER OF STRENGTH

(For The North Staffordshire Magazine, December, 2010)

In a town that has witnessed so many changes since the 1960s, the old tower of St Giles' church in Newcastle still looms large, a familiar landmark rising above the hurry-scurry of traffic on the A34. Yet even St Giles has known many vicissitudes in a history that dates back to the 12th century. A former churchwarden and historian, J. T. Coulam, wrote that there were five churches on the site of the present St Giles, which was designed by George Gilbert Scott and erected between 1873-6. The last four have been built against the same tower.

At one time, a footpath led through the churchyard of St Giles, and many people used it as a means of reaching nearby properties. However, by 1837, discussions were being held by the respectable inhabitants of Newcastle, concerning the desirability of closing it. The churchyard was becoming a magnet for the dregs of society, and memorials were being desecrated. The graveyard, it was stated, was "a common resort for the most filthy and dissolute characters and was in fact a harbour for all those who during the night wished to screen themselves from the public eye."

The state of the churchyard became a pressing concern in the middle of the 19th century, when King Cholera ruled in Newcastle-under-Lyme. Ten people died within 20 hours in Church Street, and Lower Street was dubbed the Valley of Death. The fact that the graveyard was full did not help the sanitary condition of the area. Many coffins were buried on top of each other in the same plot in order to conserve space. Mr Barratt, a gravedigger, reported that on one occasion, he had dug a plot to the depth of 10 ft when a mass of earth fell on him, dislodging some human remains and decayed coffins, as well as the coffin of a child. Barratt was taken ill with cholera that same day.